This material is available in other languages:

ru

23 Jan 2025

Chechnya was named the safest region of Russia for the second time. Is it really that safe?

Фото: cityreporter.ru

Table of contents

- The Case of Zarema Musayeva

- The Case of Magomed Abubakarov

- Mass Abductions

- "Cleansing Operations" and forced conscription for war

The Ministry of Internal Affairs has once again recognized the Chechen Republic as the safest region in Russia, citing a low crime rate: 17 crimes per 10,000 people in 2024.

"In Chechnya, there are fewer reports to law enforcement agencies than the national average. <...> The problem is that violence mainly occurs where the state does not see it — at home," note representatives of the human rights organization “Marem” (A human rights organization that focuses on documenting and addressing human rights violations in Chechnya, particularly issues related to violence, abductions, and state repression.)

As an employee of the “Hot Spots" division shared, the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ statistics do not reflect crimes committed by representatives of the Chechen authorities and law enforcement agencies.

"Abductions, detention in illegal prisons, torture, extortion, public humiliation, threats, attacks on journalists and human rights defenders, murders of those who don’t conform — all these acts, which have become an integral part of the repressive system, do not appear in the official crime statistics," said a human rights defender from the Memorial Center.

The right to commit violence in Chechnya has effectively been "usurped" by security forces and those in power. Their actions remain unchecked, as victims are afraid to seek protection, knowing that instead of punishing the perpetrators, they themselves may become targets of persecution. Only the most desperate, those who have nothing left to lose or those who have managed to flee, dare to speak about such crimes.

Even among those who have left, far from everyone is willing to raise their voice due to the risk of retaliation against relatives remaining in the region, the mechanism of "collective responsibility" continues to operate.

Moreover, as “Marem” points out, if people in the republic do not turn to the police, and women remain completely silent about the violence committed against them, this creates the illusion that crime does not exist.

”Just as there is no Seda Suleymanova, who supposedly 'ran away from home again.' Just as there are countless other women who never had the chance or were too afraid to seek help," writes “Marem”.

We have repeatedly written about cases of relatives of bloggers and critics of the authorities who are outside of Russia being kidnapped, as well as about the abductions and murders of those deemed undesirable. Those who disagree are killed not only within the country but also far beyond its borders.

All these facts confirm that in Chechnya, the "Kadyrov order" imposed by Vladimir Putin is enforced not by law, but by total fear, in which Chechens are forced to live.

Here will be presented only a few stories from the life of the "safest region," which we have written about many times before.

The Case of Zarema Musayeva

Zarema Musayeva in court. Photo: Elena Afonina / TASS

The wife of former judge Saidi Yangulbaev was abducted on January 20, 2022, from an apartment in Nizhny Novgorod and taken to Chechnya as a witness in a criminal fraud case. However, a criminal case was ultimately opened against Musayeva herself: according to the investigation, she scratched the face of a law enforcement officer while in police custody. The court sentenced her to 5.5 years in prison, though the sentence was later reduced.

On November 11, 2024, Musayeva faced new charges for "disrupting the operation of institutions ensuring isolation from society" (Part 2, Article 321 of the Criminal Code). Under this article, Zarema faces up to five years of imprisonment.

Musayeva suffers from a chronic illness, insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes, and has difficulty moving even with a cane. Her health has only worsened while in detention.

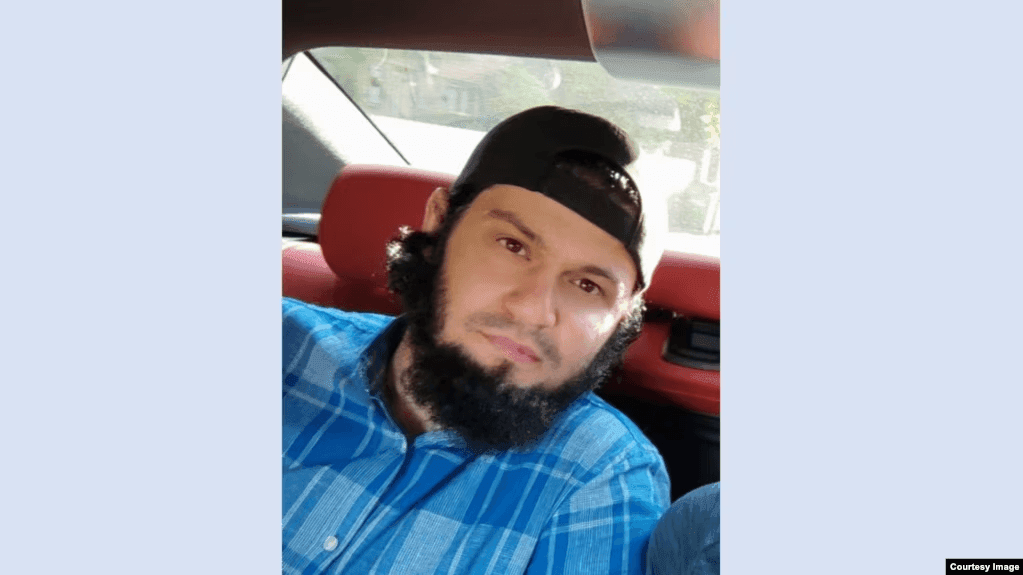

The Case of Magomed Abubakarov

Magomed Abubakarov

In 2023, the Memorial Center reported the abduction of three residents of Urus-Martan, including Magomed Abubakarov, who was 32 years old at the time. He is a British citizen who had been living in the UK with his wife and children.

In 2024, Memorial Center sources revealed that Abubakarov was prohibited from leaving the republic and was later wounded during his arrest. He underwent a complex surgery and was placed in intensive care. Security officers were assigned to guard him, and he was charged with using violence against a government representative (Article 318 of the Criminal Code) and illegal possession of weapons (Article 222 of the Criminal Code).

Mass Abductions

Chechen Telegram channels reported that between May 6 and May 14, 2024, between 80 and 90 people were abducted in Chechnya.

Bloggers link these abductions to a video published on May 6 by several Chechen Telegram channels. The video shows an unidentified man, whose face is blurred, setting fire to a Lada Niva car with the word "Dustum" on its license plate. This was the nickname Ramzan Kadyrov used in his youth, and recently, his son Adam has also been referred to as "Dustum."

With the help of volunteers, we gathered information on the reasons, circumstances, and probable identities of those abducted.

"Cleansing Operations" and forced conscription for war

On October 24, near the village of Petropavlovskaya in Grozny District, a column of the Russian National Guard was shot at. According to the official version, one officer was killed and another was wounded. Shortly after the incident, security forces resumed the practice of "cleansing operations."

In all inhabited localities near the village, officers of the Russian National Guard and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (police officers) conducted house-to-house inspections, checking residents' documents and ensuring no unregistered individuals were living there. They also verified vehicle registration documents.

At the slightest violation of the norms and rules established in the Chechen Republic, men deemed fit for deployment to the so-called "special military operation" (SVO is the abbreviation often used in Russia) were taken to police stations. Their phones were confiscated, and if any evidence was found of them accessing Telegram channels critical of the Chechen authorities, they were detained. Reports from various police departments indicated that detainees were given a choice: either go to the front or face criminal charges.

For more information on human rights violations in the Caucasus region, visit the "Caucasus: Hot Spots" section.